I’ve been thinking about alignment in tabletop RPGs a lot lately. It came up because the game that I’ve been playing lately, Pathfinder: Kingmaker, has an incredibly clunky alignment system that pushes characters towards lawfulness and goodness (on a 9-alignment system of good vs evil and lawful vs chaotic with neutral separating each alignment from the others) because the basic assumption is that a decent person is “neutral good.” Anything that is a little orderly is lawful, anything even a bit self-oriented or anti-established norms is chaotic, anything other than being decent is neutral, and anything absolutely reprehensible is evil. I disagree on so many levels it is difficult to find a place to start other than the very basic assumption: I think most people, even allowing them to be decent human beings, is “true neutral” or unaligned.

Continue readingTabletop Gaming

Player Engagement Is a Key GM Skill

I have not always been a good DM. I think it might still be presumptive to call myself a good DM and that I would be more comfortable saying I’m a decent DM with a few specialities, but I think I wouldn’t argue against anyone if they called me a good DM. I think the lesson I learned that made me an alright DM was to never, under any circumstance, take away player agency. They’re free to do whatever they want in the game and I should support their endeavors, but they’re also free to suffer the consequences of their actions.

Continue readingPost-D&D Glow

There’s nothing quite like that post-D&D Session high. It’s like exhaustion, a headache, and a stomach bug all rolled into one. Basically a hangover. So incredibly unpleasant, but a sign of great times now over.

I don’t really drink much these days, so maybe that’s me romanticizing my early to mid twenties than a reflection of how I feel about hangovers, so maybe don’t drink to excess.

Continue readingMaking a Monster

Creating a good D&D 5e homebrewed monster is a matter of balance. Like all things within the bounded-accuracy system of fifth edition, most of the specific numbers for attacks, armor class, and attributes are unnecessary. What you need to know is how to land within certain likelihoods for damage input and output, understand how to balance the action economy of fifth edition, how the difficulty of a fight is set, and the purpose of legendary/lair actions. While this seems like a lot to keep in mind, most of it falls under a series of general rules that make it easy to adjust a fight as it happens so you wind up with what you, the Game Master, expected.

Continue readingVisible Versus Hidden Dice Rolls

When it comes time to make a skill check, every DM faces an eternal conundrum: do you let the players roll it or do you roll it? Is it better to allow the players to make every roll for every check, save, or attack or is it better to keep some of them to yourself so they don’t influence the way your players choose to act in the moment? Sure, there are roleplayers out there who won’t flinch at a botched stealth roll or who can resist summoning dreadful images in their head if they roll single-digits on a saving throw, but most people aren’t that good at separating what they know from what their character knows or can infer.

The Trials and Travails of Playing Dungeons and Dragons

Most of the time, I don’t play D&D. I run it. There’s a pretty big difference. As a DM, running D&D requires an understanding of the style of game you’re playing, a hefty knowledge of the world you’re playing in, a grasp on at least the core concepts of the rules (though an encyclopedic knowledge of them is frequently very helpful), and at least several reference documents because there is no way you’ll know everything you need to know off the top of your head.

It’s a numbers game with lots of narration and storytelling that requires you to set aside your ego so you can provide opportunities for your players to explore the world, tell a story, and try things. Generally, you want to avoid a focus on “winning” as the DM and instead focus on making sure everyone is having a good time. There’s a lot of social management since it is frequently up to the DM to intercede in arguments or interpret rules that don’t necessarily have a clear answer to the question the player is asking, all of which requires a certain amount of social consciousness as the DM. You need to watch your players so you can be ready to support them as they need it and challenge them as they want it. When you DM a lot like I do, it can be easy to think of playing as something that is incredibly easy.

When you get a chance to play though, and really get into it, your perspective shifts. Suddenly, you’re not thinking about managing numbers, turn order, and a thousand tiny details but trying to manage your expectations. Instead of trying to anticipate the players, you’re trying to navigate the minefield that is a combat encounter. Especially at low levels, one wrong choice can make the difference between a simple fight and a fight that uses up all of your resources and abilities. Whenever you’re confronted with a door, there’s no way to know what is behind it and, if you’re the leader of your sorry bunch of misbegotten misbegots, it falls on your to decide if you should open that door or if you should take the safe route and find a place to hunker down until everyone’s hit points are full.

While the effort involved is vastly different, the toll isn’t. As a player, you don’t have to manage a thousand little details, but your character’s life hinges on the success or failure of your actions. As DM, you don’t need to emotionally invest in each decision because there’s no risk of failure for you in a combat encounter. Your job is to help tell a story and provide a challenge. As a player, making the decision to stand at the back of the group is fraught with danger. If, like my character was today, you’re at half hit points and facing a swarm of creatures that aren’t tough but could easily overwhelm you when there’s over ten of them to your single you, that decision isn’t an easy one.

You, the player, don’t want your character to die, but sometimes that’s what happens. Sometimes characters die because of the choices they make. And I say “they” because I, personally, would not choose for Lyskarhir the Elven fighter to stay behind the group of villagers as they flee the church they’ve hidden inside, but Lyskarhir the Elven fighter certainly would, even if he’s a cantankerous asshole. They didn’t ask to have their town wrecked and their loved ones slaughtered in front of their eyes, and most of them aren’t up to the challenge of standing firm in the face of an oncoming hoard, but you are. So you stand and hope they get away quickly enough for you to get away instead so you don’t need to find out if you’re the kind of person who’d let someone else die instead of facing an attack you’d probably survive.

I, personally, wouldn’t choose to keep Lyskarhir exposed to danger so that as many of the enemies focus on him instead of the fleeing villagers, but Lyskarhir sure would. He knows he can probably get away and, once the group splits, idly walk up behind them with his longbow out and kill them as they chase the defenseless townsfolk. I, personally, know Lyskarhir can do this and Lyskarhir’s battle strategies are only as good as my strategies, so I let Lyskarhir decide what to do and does his best to fight the duality of his mind so that he (I) can properly roleplay.

As a DM, roleplaying is swapping masks to be whoever the players are talking to. If you’re really good at it like Matt Mercer, you can become entirely new people with every new character. If you’re just alright at it like I am, you can try to change the tone of your voice and at least make them use different words to help the players see the difference between the people they’re talking to. When you’re playing, you’re putting on a mask, a costume, and assuming an entirely new persona. You have to manage the difference between what you know (which, as a regular DM, I know EXACTLY how many hit points each monster we fought had) and what your character knows. Lyskarhir doesn’t know that kobolds have five hit points, but he does know that not a single one has survived being shot by him. I, peronsally, know that Ambush Drakes don’t deal much damage, but all Lyskarhir knows is that there is a pair of wolf-sized dragon-ish lizards running toward him at an alarming pace.

As much as I enjoy storytelling and being a Dungeon Master, I will never be as excited by a gameplay moment as I was when my Elven fighter survived four wild swings, three of which missed thanks to his excellent planning, that left him with one single hit point and the final attack he needed to take down the champion of the enemy forces. Even if the DM let me get away with 1 hp because I’d gotten lucky enough to reduce an enemy that should have wiped the floor with me to the single digits, it won’t change how great it felt to emerge victorious from a fight that went better than it had any right to.

Now, three hours after the fight concluded (which is when I’m writing this), I am still jittery and excited about that moment. I want more. I’m reminded of how much I love playing, of the highs and lows of tabletop gaming that you feel as a player who can only do their best in the given situation. I miss it. I wish I could get more of it. But it also feels pretty great to be reminded of the experiences I can provide to other people when I run games for them. I just hope I get to keep doing both as the world shifts and changes in the face of this pandemic.

Bringing Social Distancing to Your TTRPG

Planning your next Dungeons and Dragons session but unsure how the burgeoning pandemic will affect attendance? Wondering how much Purell you’ll need to clean all your dice after you roll them on the table? Unsure how to handle taking turns to bring the food when your increasing paranoia about getting sick has granted you the ability to see the germs wafting out of everyone’s mouths as they breathe?

Tabletop Highlight: Dice and the Laws of Probability

If you pick up and roll a d20, you have a 1 in 20 chance of rolling any given number. If you pick it up again and roll it, you have a 1 in 20 change of getting the same number despite the fact that, if you’d considered this from the outset, you’d have had a 1 in 400 change of rolling the same number. If you rolled it a third time, it’s still 1 in 20 as roll it but, as a concept, is also 1 in 8000.

Mathematically speaking, the 1 in 8000 chance represents all potential outcomes for rolling a twenty-sided die three times in succession with the goal of it being the same number each time, but technically only if you pick which number it is in advance. If you say “any number” three times, the chance is really 1 in 400 because the first roll just sets the target number rather than affecting the probability of getting it three times in a row. But, if you talk about it afterwords, you still had a 1 in 8000 chance of rolling that exact sequence.

Clearly, the probability of this is a bit fucky because anyone who has played D&D can tell you, you do not need to roll a d20 8000 times in order to roll three natural twenties in a row. In 5e, this exact sequence is a little less remarked upon because if you roll a single “natural” 20, you critically succeed at whatever the roll was about (some variations on this apply since that’s technically a house rule that is widely used rather than a rule suggested by the D&D books). You don’t need to roll anything else. In the previous popular version of D&D, 3.5, you had to roll to confirm your critical hit and almost everyone played with the custom rule that rolling two 20s in a row mean you went from scoring a critical hit to potentially killing your target with a single hit. If you rolled a third 20, your target was just dead because it had been made clear the dice gods wanted them dead.

As a DM in charge of NPCs in combat and in social encounters, I typically make more dice rolls than any one of my players. As a result I have a tendency to see more extremes than most of my players. That being said, it doesn’t account for my ability to roll three natural twenties as frequently as I do. I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve roll three natural ones in a roll because the number is zero. The most I’ve ever rolled is two. Yet I’ve also rolled five natural twenties in a row. I also have a high tendency to roll in the upper third of numbers on any standard die I roll. I like to joke with my friends that prettier dice roll better, but it doesn’t matter for me. Any die I pick up can do this.

I can’t explain it any way but this: I have a huge amount of dice luck. It doesn’t apply to any kind of chance-oriented situation since I’ve only ever won one thing in a drawing or lottery, and I don’t think I’ve ever been dealt a decent hand in any card game, but I always roll high with dice. Specifically, high. Not “well.” My friend was working on a game where you needed to roll under certain numbers in order to succeed and I failed literally every check I ever rolled in the two 3-hour sessions we played that game. For whatever reason, I roll high on dice.

Which is an incredibly frustrating knack to have as a DM. I’ve killed more players due to my own good dice rolls than because of my players’ poor roles or bad decisions. As a player in other people’s games, it can be frustrating or seem like cheating when I succeed with aplomb more frequently than the rest of the table put together. I’ve been called on it a dozen or so times and now I just roll my dice in the open as a player. If they call me on it then, I offer to re-roll with anyone’s dice and still, I succeed. This is one of the reasons I always get nervous about the idea of playing in a game shop. It only takes one person losing their temper and accusing you of cheating to make you not want to play with strangers any more.

So when I roll three twenties in a row and insta-kill two player characters, I sigh heavily and move on with my life. As do my players. It’s not like I tried. I didn’t choose to be an outlier on the bellcurve that is the laws of probability.

I actually took a statistics class in college, back when I was studying psychology, and I have to say that most statistics and most probability is a bunch of bullshit when it comes to explaining how the world works. Statistics are helpful because they are part of understanding how the world works on a conceptual level, but all you have to do is look into the Monty Hall Problem to realize it is a difficult science with far more factors than is readily apparent which makes it far too complex for most of us to understand without a great deal of explanation.

Anyway, the real purpose of this piece is so that I have something I can link to when my players complain about how frequently I roll natural 20s in our D&D games and so other people can appreciate that yes, sometimes your luck really is just that good/bad. You have no one to blame for your dice rolls but yourself since not even the uncaring mathematical universe controls them as we can clearly see from the fact that I just dumped out my bag of d20s at my desk and had five twenties out of the 27 dice I rolled.

Tabletop Highlight: The World of Fifth Edition

In the past year, I’ve begun running a lot of fifth edition D&D. I’ve spent several hundred dollars buying books, PDFs, and a subscription to D&D Beyond (which is where I bought said PDFs). I’ve also bought myself a tablet for DMing, backed a number of kickstarters for easy terrain or pre-made graphical maps, figured out how to use Roll20, and started designing my own digital maps. Out of everything I’ve done this year, I think only my job has gotten more time and attention than Dungeons and Dragons has from me. I also think I’ve spent more money on D&D and D&D paraphernalia than I’ve spent on anything that isn’t a bill or food. I’ve probably spent more on D&D than takeout or eating out, at least. Those books are expensive and I just had to buy myself all the spell cards even though I never get to play D&D and just use D&D Beyond to look up the spells I haven’t already memorized when I’m DMing, either in the general search or through the helpful spell description windows that open when you click on or hover over a spell.

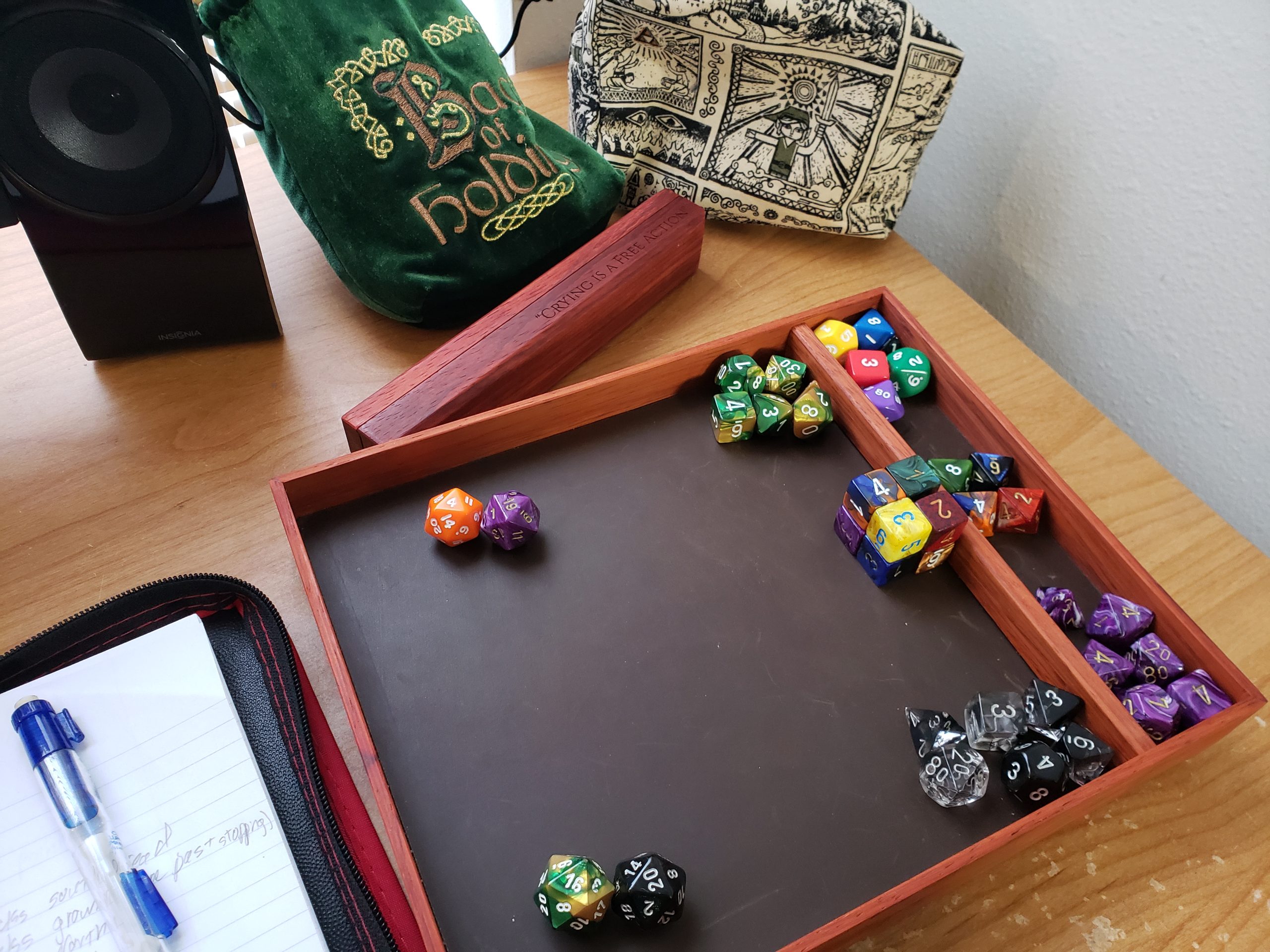

Tabletop Highlight: On the Importance of Dice

I am a firm believer in the importance of dice in tabletop RPGs. To be entirely fair, that’s not exactly an uncommon opinion, even if more people are moving toward digital dice rollers instead of actual rice. Sure, telling a computer to roll twenty six-sided dice makes it a lot cleaner and it does the math for you which makes it take less time, but there’s no feeling compared to being a twentieth level sorcerer casting disintegrate just so you can roll forty six-sided dice all at once. At one point, I literally had bought enough d6’s so I could roll damage all at once for my caster. It was an amazing feeling, making it rain dice like that. It was also incredibly difficult since I could barely hold that many at once and rolling them involved a lot of me saying “did anyone see where the beige one went?” and my friends replying “no, but I did find the purple one from last week under this radiator.” Good times.

All that aside, what I’m really talking about is the importance of specific dice, which is also a bit misleading since I’m not thinking of one specific die in all of creation. What I’m talking about is the importance of having specific dice for you to use. By our very nature, as creatures reliant on ephemeral chance to dictate the course of our gaming session, we tabletop gamers are a rather superstitious bunch. For instance, I not only have a favorite set of dice, but I pick the dice I use on any given night by how aesthetically pleasing I find them as I get ready for the game. I firmly believe that prettier dice roll better and no amount of bad luck on my more gorgeous dice can shake that belief. The inverse is also true. When my players are having a string of bad rolls, I swap to using my ugliest, most generic and awful dice so the enemies the party is facing roll worse. My absolute favorite set, the set that has rolled more triple-twenties than all of my other twenty-sided dice put together, is a beautiful set of clear plastic dice with bits of black paint or plastic swirled inside them. Unlike every other set of partially clear dice I’ve ever seen, the color is only on the inside of the dice. It doesn’t touch the outside layers at all, so you can spin the dice as you hold it up to the light and watch the smoky black color swirl at your fingertips. I don’t even let other people touch those dice. I keep them in a plastic container inside my dice bag so I’ve always got them ready to go in case I need to roll well on something important.

If you take a survey of all tabletop players, you’ll find a range of traditions and superstitions. There are players who believe in punishing their dice when they roll poorly and even destroying the dice if they keep rolling poorly after being punished. This punishment can range from something as mild as leaving the offending die on its own for a while to the incredibly gross tradition of putting one of your misbehaving dice inside your mouth for a while. I’ve even seen someone go so far as to file through a die they were punishing so it could never roll again, which just seems completely over the top to me. There are also people who believe that you need to roll all of your dice at once, regardless of how many that might be. I’ve got a friend who uses a specific die for every type of action his character might be taking in any game he’s playing, so he has to buy new dice every time he plays a game with an additional action type. I prefer to buy new dice for characters who are about to make their debut, so the character and the dice start off fresh. I generally only get new dice for characters who are supposed to be a part of a campaign for a long time and I do it to avoid any kind of mental influence on how I see the dice.

Despite the range of beliefs and the things people do with their dice, most people remain a bit more rational and logic-oriented than their superstitions suggest. I bet if you followed up your first survey with a second survey asking people if they though there really was something to their little traditions, almost everyone who answered the first one would say “no.” And yet we’d still turn around and immediately go back to our superstitions as soon as the situation called for it. The way I’ve always viewed it is that there’s no harm in being cautious or believing in something that’s probably not there. If it isn’t there, then you’ve just spent a bit of time marking a tradition. If it turns out that there was actually something to it, then you’ve got your bases covered already. It’s why I don’t really believe in ghosts, but I won’t denigrate anyone who believes in them. Additionally, and probably more importantly, it helps the players feel like they’re in control of what is pretty much just random luck. If you believe punishing your dice will make them roll higher next them, then you’re in control of your own outcomes because you can “encourage” your dice to get with the program. You more order you can impose on what seems like chaos around you, the better you feel.

The same is true of having specific dice for specific things. I probably haven’t rolled more triple twenties with my favorite set of dice than with any of my other sets, but the belief that I do roll more twenties makes me remember when I do. It’s simple confirmation bias. The same is probably true of punishing dice or whatever inane thing we all do that makes us feel more comfortable with the fact that the world isn’t as cut-and-dried as we’d like to think it is. Random things happen outside our control or comprehension and we get a glimpse of that when we play games with dice because the difference between success and failure is pure chance. For the vast majority of us, there’s no skill involved, no talent, just dumb luck. Even the most skilled of us, who should be able to succeed no matter what is thrown at us, can sometime fail because of chance. So roll the dice and hope you get more passes than failure.